Dear President Obama,

I know you will probably never read this letter. But, as a good Mexican, I’ve been taught to expect disappointment in advance, so there is no harm in trying.

My name is José Ángel N., and I am an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. I have lived in Chicago most of my life, and the night you were elected U.S. President I watched with my face pressed against a chain-link fence as you delivered an impassioned speech at Grant Park.

I come from Guadalajara, a city that you visited during your first official trip to Mexico as President. What did you think of my city, by the way? I have not been home in two long decades, so your memory of it is more current than mine.

Like most people, I came to the United States because I heard that people here had a chance to start over. Actually, I didn’t hear that. The news of the riches of our neighbor to the north reached me in the form of shiny cars, designer clothes, flashy shoes, and impressive electronic gadgets that people in my neighborhood brought back with them when they returned from the United States. My knowledge of America was strictly empirical. That was not, incidentally, a word I knew when I first left Mexico at 19 years of age. I learned it first in English here in Chicago when I was almost 30 years old, during my freshman year in college. And only years later did I learn its Spanish equivalent, empírico, with its ostentatious accent mark on the second syllable, which gives the word a nice rounded sound, like a bubble that first bursts in your mouth and then closes gently.

It was because of that knowledge, because I knew that, in order to afford even a decent, durable pair of shoes I needed to work and save for two months or more, that I decided to leave for the United States. Don’t get me wrong. It is not that I didn’t want to work. I’ve been working since I was 6 or 7 years old. Neither was it the case that my goal in life was to purchase designer clothes. Rather, it was because back then the Mexican economy didn’t compensate fairly for one’s labor, which made one’s hopes for building a better life practically non-existent. This is probably the case even now.

But let me explain myself. My father died at 22, just a few days after I was born, leaving my mother a widow at 16 years of age. I grew up in a crowded one-bedroom house that I shared with 11 family members—my mother, my grandmother, and nine aunts and uncles. Needless to say, poverty defined my life since the day I was born. And thus, because a person from my social background can never hope to satisfy the criteria necessary to obtain an American visa and enter the country through legitimate channels, one night when I was 19 years old, I crossed the border through a dark and filthy sewer tunnel.

Upon arriving in Chicago, I immediately set to work doing all sorts of menial jobs. In addition, I began attending ESL classes where, by mere chance, I learned I could study for something called the GED (the equivalent of apreparatoria diploma, which I would have never dreamed of being able to obtain in my dear México). For a person who had abandoned formal schooling at 13 years of age, the GED test was, I must admit, incredibly difficult, but I managed to finally pass it after three arduous attempts. By the time I started college, I had been in the States for about ten years.

It was in college, President Obama, that I became familiar with American culture and values. I learned, for instance, about the marvelous principle of freedom of speech enshrined in the Constitution. Through my readings, I eventually also learned that a large number of people have gone through great pains to deny this right to many others, that the document of the founding fathers, like the country itself, is a work in process, and that in order to bring it to its full fruition, individuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau and W.E.B. DuBois, Noam Chomsky and Cornel West were needed.

It was also in college, President Obama, that I learned about the complexity of words—how ephemeral or powerful they can be, how deceiving or uplifting they sometimes are. And later, many years later, after finishing grad school and after reading American history more closely, it became clear why in this debate over immigration a plurality of voices—some furious, some compassionate, some clueless—usually fills our airwaves and printed and electronic media, but only one is missing, that of the undocumented. Not the Dreamers, who are Americans through and through and speak perfect English, but that of their parents. People like myself, economic migrants who have traditionally not had access to adequate education and who have learned that, in order to survive, one must obey and be silent.

That, in a nutshell, is our story: the story of a minority confined to silence.

All of this is why, Mr. President, I am writing you this letter—to let you know that we are learning your language. Not so we can curse, like Caliban, and return the insult to those that label us “illegals” and deem us lesser human beings. Rather, it is so that we can converse about our mutual problems, sustain civilized discussions, argue passionately perhaps, and reach a common solution.

We could ask questions. For example, how is the case of the 11 million of us currently leading clandestine lives in the U.S. different from that of some of the first Americans going west, following Stephen Austin’s lead to settle in Mexico, “passport or no passport”? Or, would those thousands of children fleeing violence-torn Central America be turned back if they were arriving at Ellis Island from Europe a hundred years ago instead of showing up now at the Mexican border? Or, is this a better country after over two million families have been broken apart? Or, could my three-year old daughter be the next American child to lose her father to deportation?

Just a couple of weeks ago three leaders of the business community came out in support of an immigration reform. They believe immigration should favor foreign capital and talent. Shortly before, Mr. President, you had made the case for a more traditional immigration reform, one that empathizes with working men and women rather than with privilege. This, I believe, is more in line with the everyday reality of the country. Most of us have not come looking for a place to deposit our investment, but for a fertile soil where our frustrated hopes might flourish. Some of us have managed to find relative stability, but at the price of our human dignity.

In my own case, Mr. President, rather than riches, I found your language, your books, your universities. Just like you, in Chicago I found my wife, and it was in this beautiful city that my daughter was born. Chicago gave me a chance to reinvent myself, and now, more than 20 years after arriving here, I still long to call it home.

Toward the end of the summer, President Obama, when you reconvene with your group of advisors on immigration, you’ll have a chance to alleviate the suffering and uncertainty of millions of people who have been contributing to the wellbeing of this country for many years. I hope your advisors offer you powerful enough reasons to take action, and I especially hope that you find the courage to follow your own convictions.

Respectfully,

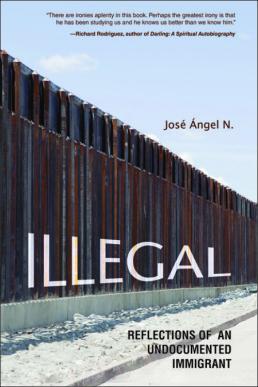

José Ángel N., author of Illegal: Reflections of an Undocumented Immigrant