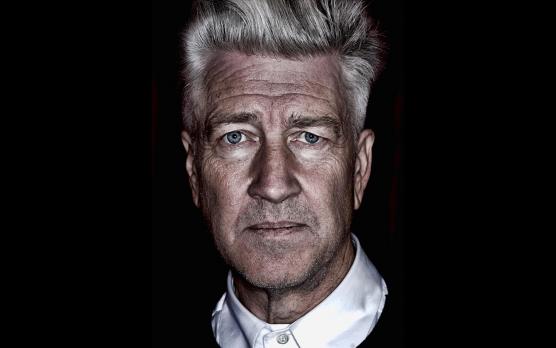

Dear Mr. Lynch,

Beyond the joy of creation, recognition, and the obvious benefits of fame like money and girls, I think the biggest ambition of any artist is to gain the respect of the guys who influenced them. To be considered an equal by them for just five minutes. To talk as peers.

Mr. Lynch, you’re on my short list. However, the road to fame is long, hard, and wrought with happenstance, obstacles, luck, and a zillion other x factors out of my control. I just might not ever make it. And even if I do, I might not ever do anything up your alley. And, not to be crass, but you’re getting up there in years. So, in the unfortunate and likely event that our paths never cross, I figured I’d at least send this little message out into the ether. Maybe you’ll pluck it out of the universe one day while you’re meditating. Or maybe you have a friend who’s a huge Smug Film fan. (Hey, I can dream, can’t I?!)

The reason I’d like to have a little sit-down with you, apart from the fact that you seem like a nice and interesting guy, is because I think you’d get a kick out of my first experience with your work. It was very, for lack of a better word, Lynchian.

When I was 13 and really starting to get into movies, my dad told me about a movie called Eraserhead. This was 1999, right around the advent of a new technology called DVD. We actually bought a DVD player because my grandma accidentally bought me 2001: A Space Odyssey on DVD. (She thought it was the soundtrack on CD.)

This was long before you released Eraserhead on DVD—one of the best special edition releases of all time, I might add. The presentation is amazing, the extra features might be my favorite of any disc in history, and even the menus are a work of art.

Anyway, my dad was on a mission to show me Eraserhead, so he tracked down a VHS bootleg on eBay. It had a little timecode burned into the upper right corner and came in a clear white hardshell case. I laid down on the couch and started it up, and I guess I was exhausted because I fell asleep around the thirty minute mark. You might be thinking, ‘Thanks a lot, kid.’ But here’s the thing—I dreamed. And it’s the only time in my life I have ever dreamed in black and white. I dreamed the rest of the movie as it played before me. In my subconscious version, Henry drove a car. There was a gun and a darkness and the baby was a monster. There was blood and fear and shadows. Henry was sad and nervous. And he was in his car, running from something.

I could listen to you talk for hours. Actually, I have. Sometimes I put your 90 minute interview about the making of Eraserhead on and listen to it on loop while I work. I don’t think you’re as weird as people think you are. I also think you’re weirder. People think you’re weird because you make “really fucked up movies”. To them that’s a good thing, and that’s not bad, I guess. But, it’s reductive descriptions like those, put out by thoughtless people who just want to see weird shit, that kill art. Understanding why and how is the best part. It’s what makes art come alive. It’s why I can listen to you talk about it for 90 minutes over and over and over and never get bored.

I’m sad that you won’t talk about Dune. Not because I’m a sadist or anything, but just because I have kind of an obsession with it. You’re right that it isn’t a great movie, but I think there’s a lot of interest to be mined there. Rumor has it you were asked to direct Return of the Jedi in the wake of your success with The Elephant Man, and it makes sense since that’s a solid movie. What might look strange historically though is that if the Jedi rumor is true, why go on to do Dune? But I suspect, like most things, there’s a lot missing from that narrative. Dune is also littered with some of your most ‘Lynchian’ visuals. The interstitial content and dream sequences are some of my favorite cinematic images of all time, and are in fact the only sequences of that kind I have ever really liked. I don’t dream in short, abstract spurts that relate directly to the goings on of my daily life. I don’t know anybody else who does either, and using those as a device in movies always seems like such an easy (and I mean easy in a bad way) approach to doling out emotional exposition for a character. But the sequences in Dune have so much personality that they make me wonder if everybody else just does them wrong.

This leads me to what I end up telling everyone when you come up in conversation: David Lynch is my margin of error. He is my proof positive that abstraction in art can be good, even transcendent. Art should be abstract. Its justification for existence is its perversion of reality. The DeLorean time machine is an abstraction, and so is the magic baseball field. But because those movies are entertaining, we don’t consider this abstract. Some of us don’t even consider it art. The irony is obvious. The connotative version of abstraction is a rebellion against the ‘safe’ abstraction of transcendent art like Back to the Future. And when you fall into that black hole, you get Tree of Life or Empire; movies that are just a bunch of footage. In order to appreciate a movie like Tree of Life you must first understand the movies it is rebelling against. Namely, every normal movie ever made. ‘If movies generally look like X, then I’ll make Y to show that movies can be Y’. But the ideas stop there.

Eraserhead is a movie that opens with many minutes of complete nonsense, yet it isn’t just a bunch of Y abstraction. There is a linear logic, there is an arc, and there is an emotional connection. It’s probably the first movie that scares you solely with its tone, and it puts you inside rooms with sound. There’s nothing more Lynchian than the soundscape in Mary’s parents house. It’s not just that you can feel Henry’s anxiety—you are anxious with him. And every single detail is building that anxiety. The lighting is lush, crisp, and focused, so that the contrast is high yet organic. Portions of the frame that are dark are so because of a lack of light; something is there, but hidden. The compositions are wide and elegant and, most importantly, objective. Nothing is hidden from view; what could be scarier than that? The cutting is extremely slow, but in this case, the word ‘deliberate’ is more applicable. The speed of the cutting lets the bizarre soak and percolate.

Your slow cutting unlocks a device that you have essentially trail-blazed, and, proven yourself to be the only successful purveyor of. It’s the use of B Roll to create tension within a scene. In the scene I’ve been talking about, there is a cut to a light that’s flickering. A flickering light is a pretty common occurrence in daily life. But, with such slow cutting, and such overwhelming sound, you’ve managed to turn the mundane into a meaningful and chilling event. That is a mark of true brilliance in cinema. It is also way ahead of its time, and is a style that has since been copied, unsuccessfully, to death.

The point here is that that shot of the light pulsing should’t have an effect. But you’ve managed to construct a very small and intimate universe where it not only works, but is advanced. It’s a new way of looking at filmmaking, where the arc is there, but sometimes buried under expressive feelings. You’ve carried this maxim through all of your work; it’s in Dune, it’s in Blue Velvet, it was, unfortunately, done to death in Inland Empire, and it helped create one of the moss beautiful universes in all media in Twin Peaks.

There is no place on earth anybody would ever want to live more than Twin Peaks, Washington. Twin Peaks is a state of mind. It’s the idea of idyllic, American wilderness living where the people are nice, the coffee is hot, the diners are filled with delicious pie and the underbelly is terrifying (but it’ll all be okay, right?)

There’s a shot of a street light in Twin Peaks that has always stuck with me. And a shot of some pine trees dancing in the wind. They make me misty. It’s because Twin Peaks, as a state of mind, is what moviemaking (yes, I know it’s a TV show) can do best when being transcendent. It puts you into a feeling that you would want to be in. It’s wistfulness on film. Twin Peaks is the place we, as humans, want to be. We want to feel comfort. Comfort in our friends and neighbors, and comfort in the organic earth that bore us. That street light is the toll booth on that road, and those trees are the wind that will carry us there.

Your best movie might be The Straight Story, although it’s probably not. And I’d love to be great enough to be able to make an entire movie out of the thought “What if a guy finds an ear?”. The best cut in movie history is when Dennis Hopper abruptly cuts out of the room, rather than physically leaving it, in that one scene in Blue Velvet. I love the opening of Wild at Heart where Nicolas Cage beats up that guy with the speed metal playing. And I love Mulholland Drive, especially the Angelo Badalamenti and Dan Hedaya napkin scene. I love Justin Theroux in it, and especially the scene with him and the cowboy. I love the opening shot of Lost Highway, and you picked the perfect font, color, and motion for the titles. I love the idea of Lost Highway, the VHS tape in the mail. It’s great.

As a filmmaker, you (the royal ‘you’) often sit back and watch and listen and talk. You don’t get to get your hands dirty. Whereas you, Mr. Lynch, build and create and design. Your movies always have great monsters and weirdos and objects and makeup and creations. I want to get my hands dirty too; the tactile is more intimate. I do a lot of stop motion in my basement, because it’s movies, but it’s also building. When I do it, sometimes I put on the thing on the Eraserhead DVD where you just talk. You talk for 90 minutes about the experience making the movie. It’s the most detailed and heartwarming remembrance of any event in history.

I love The Amputee, how it was supposed to just be a camera test and instead you said, ‘let’s make a short where I drain an amputee’s leg’. And your short in that project where everybody made a thing with that old wooden camera was by far the best. The flames and the changing sets! I love love love The Cowboy and the Frenchman, and I love how you subtitled that scene in Fire Walk With Me, presumably just so you could make out the dialogue under the hard music.

As I said before, I think you’re more normal than people think, and more weird. And I’d love to be able to talk to you about that in person. Not to ask lame questions like “What did you make the baby out of in Eraserhead?” but instead to tell you that I get it, and I also definitely don’t, and I love that, because for the only time in history, I feel safe in the fact that I’m not supposed to.

Thank you Mr. Lynch for all the great movies.

Love,

Greg