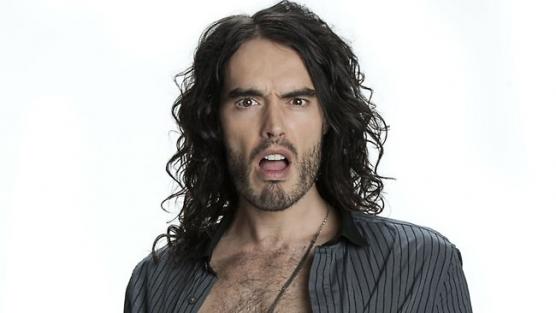

Dear Russell,

Having watched your recent BBC documentary End the Drugs War, we felt that it was necessary to address some of the points and messages contained within the programme.

While you make some very good points which we would agree with, there are other areas of the programme which can be potentially damaging to the drug policy reform movement, as well as to the people who use drugs you feature in your programme.

While we agree that the War on Drugs needs to end, and that criminalising drug users is counterproductive, even harmful to drug users and wider society, we feel that you give a very narrow view of drug dependency based on your own individual experience, and haven't fully addressed or portrayed the complexity of drug use and the many factors which contribute to, and perpetuate drug-related problems.

One of the most problematic points for us is your portrayal of both "addiction" and the "drug addicts" featured in your programme, as well as your assertion that abstinence-based treatment is exclusively the way to manage and help those who are experiencing drug-related problems. Whilst we do not demean your personal experiences with drugs, we do however question your presumption that everyone who uses drugs would benefit from this approach. For example, there is evidence that many peoples' recoveries from alcohol abuse conclude with moderate, non-problematic drinking rather than total abstinence. These people have reported experiencing problems with the spiritual focus of the 12-step program, a widely-advocated and significant part of the abstinence movement (Dawson 1996[1]; Humphreys, Moos & Finney, 1995; Klaw & Humphreys, 2000).

In your programme you state that "addiction" is a disease, and while this may be the dominant view within the medical and psychiatric professions, this is not the only, or even predominantly supported, explanation of "addiction". The Oxford English Dictionary defines a disease as "A disorder of structure or function in a human, animal, or plant, especially one that produces specific symptoms or that affects a specific location and is not simply a direct result of physical injury". For "addiction" to be a disease it would need to originate as a dysfunction in one specific part of the body; this is not the case.

Drug dependency occurs as a result of myriad physical, psychological, genetic, socio-economic, structural and environmental factors, and is not solely a medical problem. As such there is no one "cure". There are other theories of "addiction" that tend to fall into one of three categories, the "disease", "self-medication" and the "personal choice" model, all with some degree of overlap. It is important to understand the value and limitations of each conceptualization because "addiction" is still a highly controversial and politicised phenomenon.

In addition you assert that "addiction" is chronic and recurrent, as well as using terms like "hopeless" when describing the lives of those experiencing problems with drugs. This view of drug dependency which closely follows the Minnesota model (espoused by AA, NA, CA etc.) is problematic in several ways. Drug dependency is not chronic, nor does drug use necessarily lead to dependency. By asserting that it is, you are helping to create a self-fulfilling prophecy for problem drug users. Tell someone they are hopeless and they will believe it. That is not what people struggling with drug dependency need.

This narrative is in turn applied to all drug use and users, of whom, as Neil McKegany points out, the vast majority have no problems with drug use. Not only does this apply to those using "recreational" drugs such as MDMA or cannabis, but to those drug users who use heroin in a controlled way, of which there are many. In addition you emphasise drug use to be a coping mechanism for the underlying problems in people's lives, such as poverty, which are often created and entrenched by wider society. Again, this is not always the case; the vast majority of people use drugs for the pleasure they bring, and are otherwise healthy and happy people. Approximately 10% of the world's population of illicit drug users would be loosely categorised as having problematic drug use. That's almost 90% of the world's drugs users with no significant problems with their use, i.e. recreational users.

As noted, unfortunately this narrative is applied to all drugs, not just heroin, and is arguably one of the biggest barriers to policy reform at present. Your programme has partially and unintentionally fed into the very narrative that justifies the "War on Drugs". A more useful way of portraying drug use might have focused less on the extreme end of drug dependency and instead highlighted the plurality of drug use and users which exists in society, perhaps you could have interviewed people who use heroin unproblematically, or other drug users who otherwise lead normal, healthy lives. Again, by choosing to focus only on archetypal drug users, you are perpetuating the very narrative that that fuels the 'War on Drugs' you believe should end.

Unfortunately, we believe it is your singular conception of drug dependency, which leads you to the view of abstinence-based treatment as the only solution. Many people who use drugs are able to recover from heroin dependency without treatment. In addition, the often unrealistic goal of abstinence is used as criterion for access to treatment. The reality is that continuing to use drugs whilst in treatment is an automatic way of having any treatment stopped. I'm sure you can see the contradiction here.

In addition the abstinence-only view of dependency treatment leads to a phenomenon known as the abstinence violation effect. This occurs when an individual, who may have been free from drug use for some time, lapses and uses again. Rather than this being viewed as a slight relapse, the abstinence-only model greatly dramatises any small lapse. The result is that those who do lapse will tend to do so in a big way, seeing their minor slip-up as negating all their progress so far, often leading them back into regular drug use. You talk about pragmatism in your programme, however the abstinence-only model of addiction treatment is very much unpragmatic and unfair on drug users. That is not to say that abstinence isn't attainable for some, but that applying the same recovery model to every individual is unhelpful at best, counterproductive at worst.

We were shocked by your attitude towards safe injection sites as featured in the programme. These services operate to reduce drug-related deaths, and also have a track record of increasing the number of drug users engaging with treatment. Your dismissal of them as "well run crack houses" not only paints a very one-sided picture while ignoring the evidence which you could have presented (instead of relying on your initial gut reactions), but it also contradicts your earlier point about a crack house just being a "house full of poor people". This terminology adds to the negative stereotyping of drug users that is wholly unnecessary, especially if trying to take a "pragmatic approach" to the harms experienced by people who use drugs.

Again, your dismissal of methadone treatment is irresponsible. For many people methadone, in combination with psychosocial therapy, has worked. By using terms like "parking people on methadone" – a clichéd term which sounds like it originated in The Daily Mail, you are feeding back into popular misconceptions and myths. There have been numerous studies on methadone maintenance treatment. When evaluated against various "drug-free" alternative treatments, MMT has been found to consistently perform better in treatment retention and in reducing heroin use (Bal and Ross 1991; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, et al., 2003; Marsch, 1998). Furthermore, "parking people on methadone" actually has been shown to be more effective than towing people away. Patients staying in treatment for longer periods of time showed greater improvements than those who stayed in treatment for shorter periods (Sells and Simpson, 1976; Simpson, 1993). Quick fix approaches to drug dependency, which may appeal to the saviour complex in us, is the delusion that needs to be fixed.

In summary Russell, while we understand that abstinence-only treatment has worked for you, we would emphasise that drug dependency is a very personal matter that can occur for any number of reasons both internal and external to the individual, and as such the best way of attaining the outcomes desired (be that moderation of drug use or abstinence) varies from person to person.

We would also highlight that the type of drug user featured on your programme, while matching the stereotype most viewers were expecting to tune in and see, does not represent the vast majority of people who use drugs, heroin or otherwise. As a result your programme has acted to perpetuate this stereotype.

Finally your view of addiction, clearly based on the Minnesota model, which emphasises the chronic nature of "addiction", and asserts that all drug use leads to "addiction" (or at least harm) is false. Again, your opinions here have acted to reinforce the very narrative you are attempting to challenge.

We fear, and we are confident that we speak for many of those who work with people who use drugs, or who otherwise research or study drug use and drug-related problems, that your personal views may have already caused great damage, given your public status and following. While we respect and welcome your help in drawing attention to the drug policy reform debate, we would ask that you open your mind beyond your own personal experience of "addiction" and consider some of the wider research and experiential evidence before filming another programme.

We would welcome further discussion with you about any of the issues raised in this letter to help us both accomplish our shared goal of drug policy reform.

Yours sincerely,

Students for Sensible Drug Policy UK